Updated on

About the author: Thorsten Hoyer is famous in Germany for his long-distance hiking adventures. He’s also one of HANWAG’s Sole People (–> Find out more: Thorsten Hoyer profile). Originally from Erfurt, in the Thuringia region of Germany, he is renowned for his non-stop hiking exploits without sleep, and for walking the full length of Germany’s Green Belt (1,200 km along the former border between East and West Germany, which he completed in 24 days straight). (–> Find out more: Thorsten Hoyer: Hiking the Green Belt)

I love embarking on challenging long-distance thru hikes in remote parts of the world. I’ve dreamt of completing the Snowman Trek in Bhutan for over 15 years. So when I turned 50, I figured it was high time to make that dream a reality.

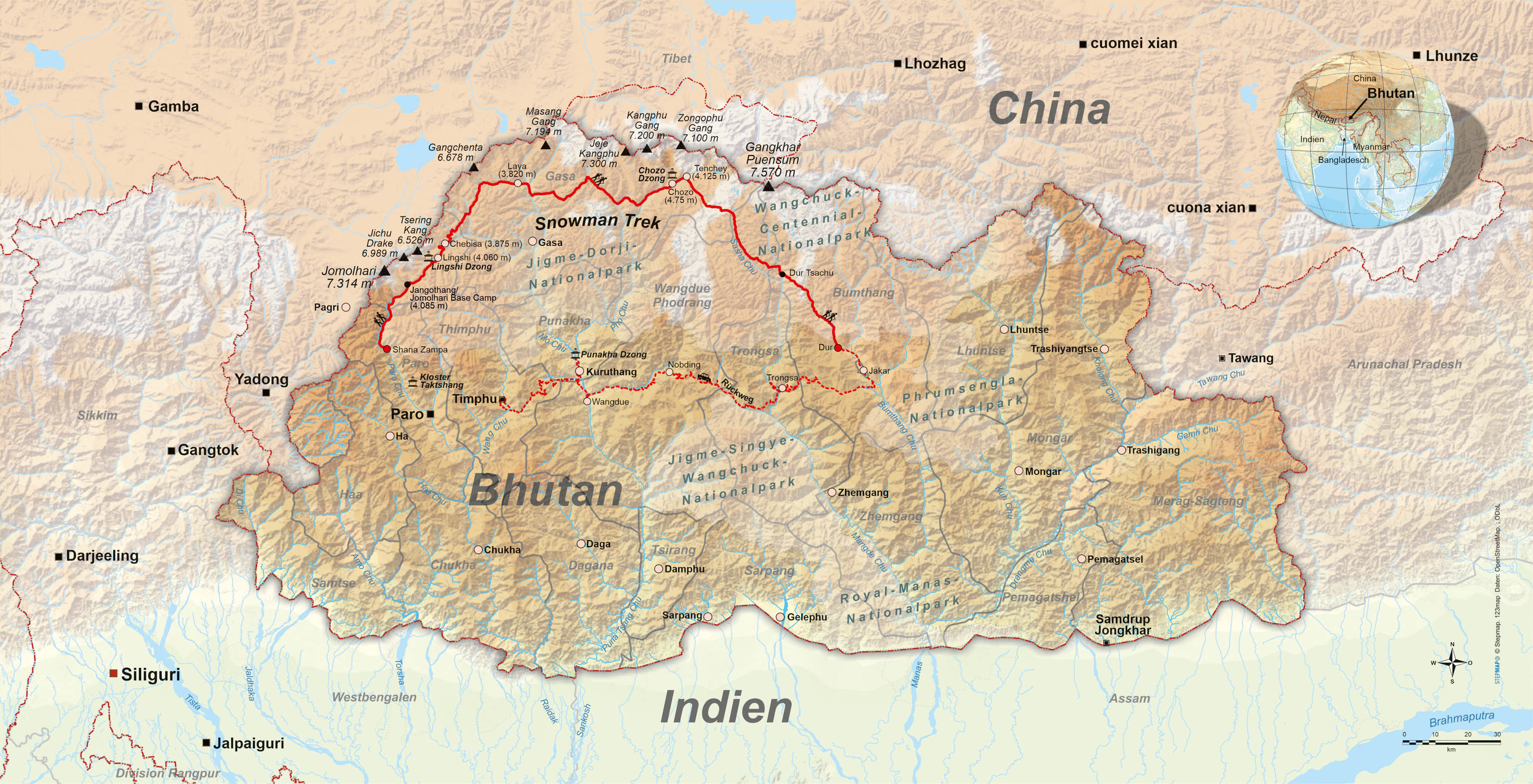

The Snowman Trek is known as one of the best long-distance hikes in the world, and also as one of the most challenging. Starting in the Paro Valley in western Bhutan the route traces a wide arc along the main ridge of the Himalayas, passing through the extremely remote region of Lunana, before reaching Bhumtang in the east of the country. It covers 360 kilometres, 14 high mountain passes and countless vertical metres, including several ascents up to an altitude of 5,600 metres.

The remote nature of this trek in Bhutan, and the unpredictable weather patterns that prevail in the region add to the challenging nature of the Snowman Trek. Reportedly, fewer than half of all Snowman trekkers make it all the way to Bhumtang. Or as Bhutan connoisseur Bart Jordans puts it: “More people have stood on the summit of Mount Everest than have completed the Snowman Trek.” But it’s definitely not about prestige; this extreme long-distance hike is far too obscure to garner recognition.

"More people have stood on the summit of Mount Everest than have completed the Snowman Trek."

Bart Jordans, author of the book 'Trekking in Bhutan'

After a three-hour drive, Pema pulls the four-wheel drive to a halt at Shana Zampa, a village in the Bhutan’s Paro Valley. From here on in, it’s our feet that will do the work – for a full 26 days, if, like me, you want to start the Snowman Trek right from the beginning. I’m introduced to the crew, made up of Sonam (guide), Yeshi (cook) as well as Dawa and Sangay (the best hosts ever). Then, there’s the so-called ‘horse man’ who’s in charge of the pack animals that will carry the gear.

Our camp is only a short distance from the Paro Chu river. On the other bank begins the Jigme Dorji National Park, one of the most important sanctuaries in Bhutan for the endangered snow leopard. But the chance of encountering these graceful creatures is next to nothing. As I get comfortable in my tent that night, I have to pinch myself. It’s actually happening. And tomorrow I’ll be setting off on this special journey. Although I can hear the sound of the Paro Chu loud and clear through the tent walls, at some point it seems to fade away, and I drift into a deep sleep.

We spend two days following the Paro Chu river, through forests of pine, oak and rhododendron. As we walk, we pass only a few houses dotted here and there, and encounter our first yaks. With their powerful frames, their horns and long shaggy coats, these are impressive creatures, but thankfully also extremely docile.

We reach Jangothang, a small hamlet built around a Chorten (a Buddhist shrine), that’s draped in prayer flags. By Royal Decree, all of the houses in Bhutan must be constructed in the traditional style. As a result, their centuries-old architecture is maintained from the smallest settlement right through to the capital city of Timphu, with its population of around 80,000.

“Mountains over 6,000 metres high are not permitted to be climbed, because they are the thrones of the gods.”

Thorsten Hoyer

The way of life here is still firmly rooted in ancient traditions and in the Buddhist faith. Out of respect, mountains that are 6,000 metres high or more may not be climbed, as their icy peaks are thought to be the thrones of the gods and therefore sacred. One of these is the 7,314-metre-high Mt Chomolhari, the mistress of the mountain gods. Following a welcome address informing us that we are “celebrating living in harmony with the ghost of the high mountains,” we spend the night at 4,100 metres, at Chomolhari base camp.

Over the following days we settle into a sort of routine: Wake up at 6:30 am with a bowl of hot water to wash with, followed by breakfast, and then break up camp and load up the ponies and mules. Trekking starts at 8 sharp. Most days, this begins with a long climb, crossing a high pass (or two) at some stage in the day, followed by a long descent, to set up camp again somewhere near a river. And just as reliably, every evening the thin cold air of the impending night drives us into our warm down sleeping bags.

Nyile La – at 4,890 metres, our first proper ‘pass’.

Bhutan (roughly the size of Switzerland) shares its borders with the giant nations of China and India. To the north, the Himalayan peaks form a boundary with Tibet. Numerous rivers carve their way down through the landscape from these peaks towards the south. Map: Conrad Stein Publishing.

But if the days tended to follow a pattern, the same cannot be said about the landscapes we travelled through. We leave the banks of the Paro Chu and cross our first ‘proper’ pass, the 4,890-metre-high Nyile La. Reaching the top of a mountain pass prompts another ritual. I place a rock on top of the pile of stones here, calling out “Lhagyelo”. It means something to the effect of “may god conquer evil”, which has the effect of energizing me and giving me renewed motivation.

The uninhabited landscape all around has the same effect, leaving me feeling anything but lonely. Instead, I am filled with a sense of tranquillity and calm. I am grateful to be following my dream. Even if it’s hard and uncomfortable at times, and even if I’m not even sure that I’ll complete it. But that’s freedom. My freedom.

“The further east we head, the more imposing the mountains become.”

Thorsten Hoyer

The further east we trek, the more imposing the mountains, and the more primal and desolate the landscape. There are fewer inhabitants in the scarce settlements we do come across, and the distances between them is greater. At some stage during our Himalayan journey, we come across a last group of nomads, sheltering from the imminent snow under a tarpaulin spanned between two drystone walls.

And then it’s just us. Diligently making our way to where the air is thin and back down again into the next river valley. Then I sit there, sipping my tea, and looking at the people and animals around me full of respect. And quite often I drift off into an almost meditative state. At least until the cold descends into the valley with the setting sun, or when Yeshi calls me for dinner.

Scheduling this Himalayan journey for the latest possible period in the year turned out to be the right decision. Although temperatures can be bitterly cold in November, especially above 4,000 metres, and there’s a possibility that some of the mountain passes will be impassable through too much snow, there’s also a good chance that the weather will be very stable, with plenty of sunshine and clear visibility.

Further reading: Hiking Germany’s ‘Green Belt’ with Thorsten Hoyer

Day 22 – the crux of our long-distance hike

New out now: Thorsten Hoyer’s book about his journey along the Snowman Trek – the full story, beautifully produced and with many more images. Conrad Stein Publishers, € 29.80, ISBN 978-3-86686-645-4

Which is just how it turns out on the crux stage of the trek, on day 22. Following a bitter cold night at 5,300 metres, the gleaming sunshine and crystal clear, steely blue skies make the snowy mountain scenery around Gangkar Puensum (7,570 m), the highest unclimbed mountain in the world, seem almost surreal.

Today is the literal, and figurative, highpoint of the trek. There are still two more high passes to cross on the Snowman Trek, at more than 4,500 metres altitude, but after that, it’s all downhill. In a steep-sided valley, we come across a torrential mountain stream which leads us to the unique little village of Dhur Tsachu. The hot springs here were originally created for the great Buddhist master, Guru Rinpoche. There couldn’t be a more pleasant place to reward yourself for your efforts of the last weeks.

“The joy and gratitude that our Himalayan trek has been a success is palpable.”

Thorsten HoyerAlthough Bhumtang is still four days away on foot, a celebratory mood of achievement sets in. In the evening, Yeshi appears with a cake, with Snowman Trek written across the top. The joy and gratitude that our Himalayan trek has been a success is palpable.

But for me, there’s also a sense of melancholy. With the words “celebrating living in harmony with the ghost of the high mountains” still floating round my head, I come home from Bhutan with yet another dream.