Updated on

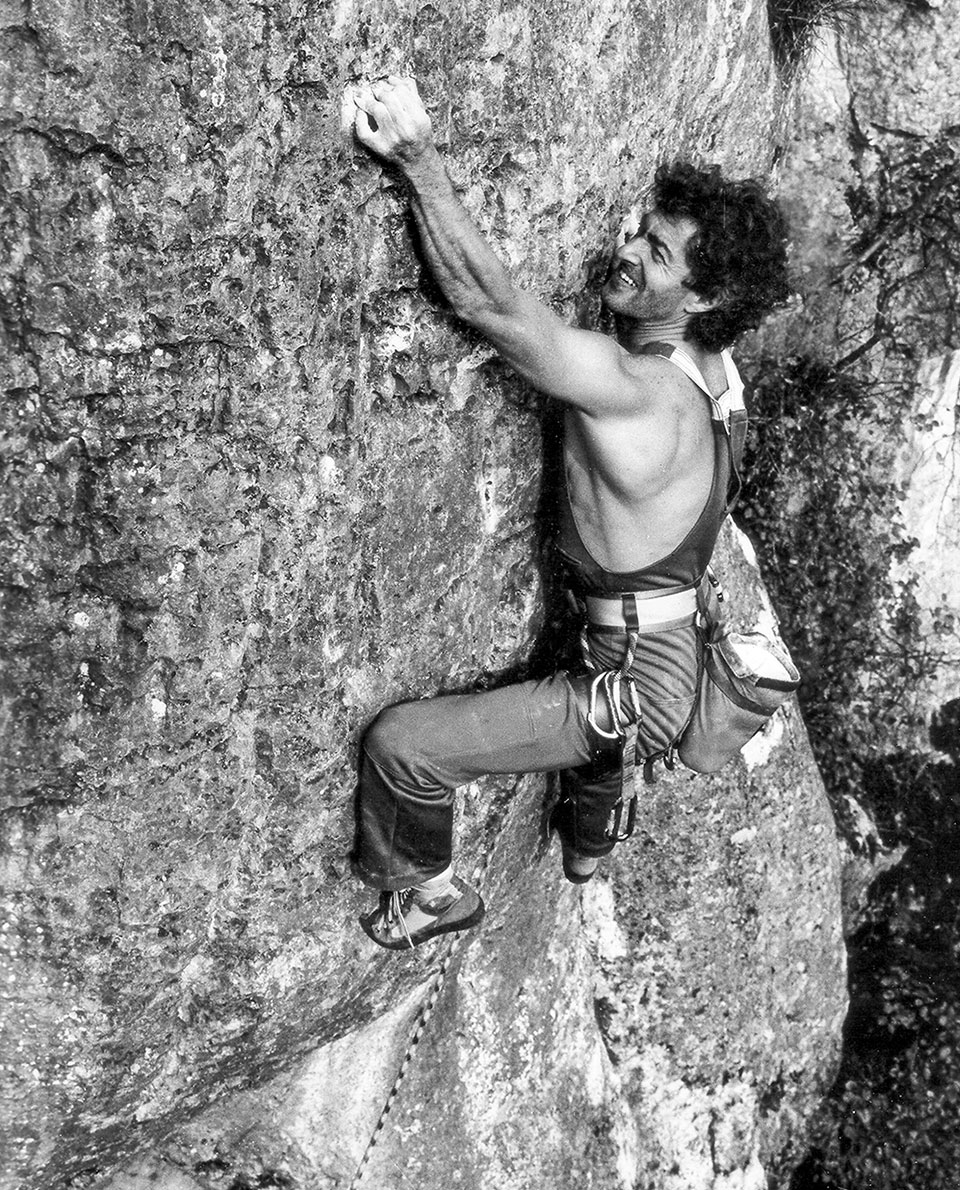

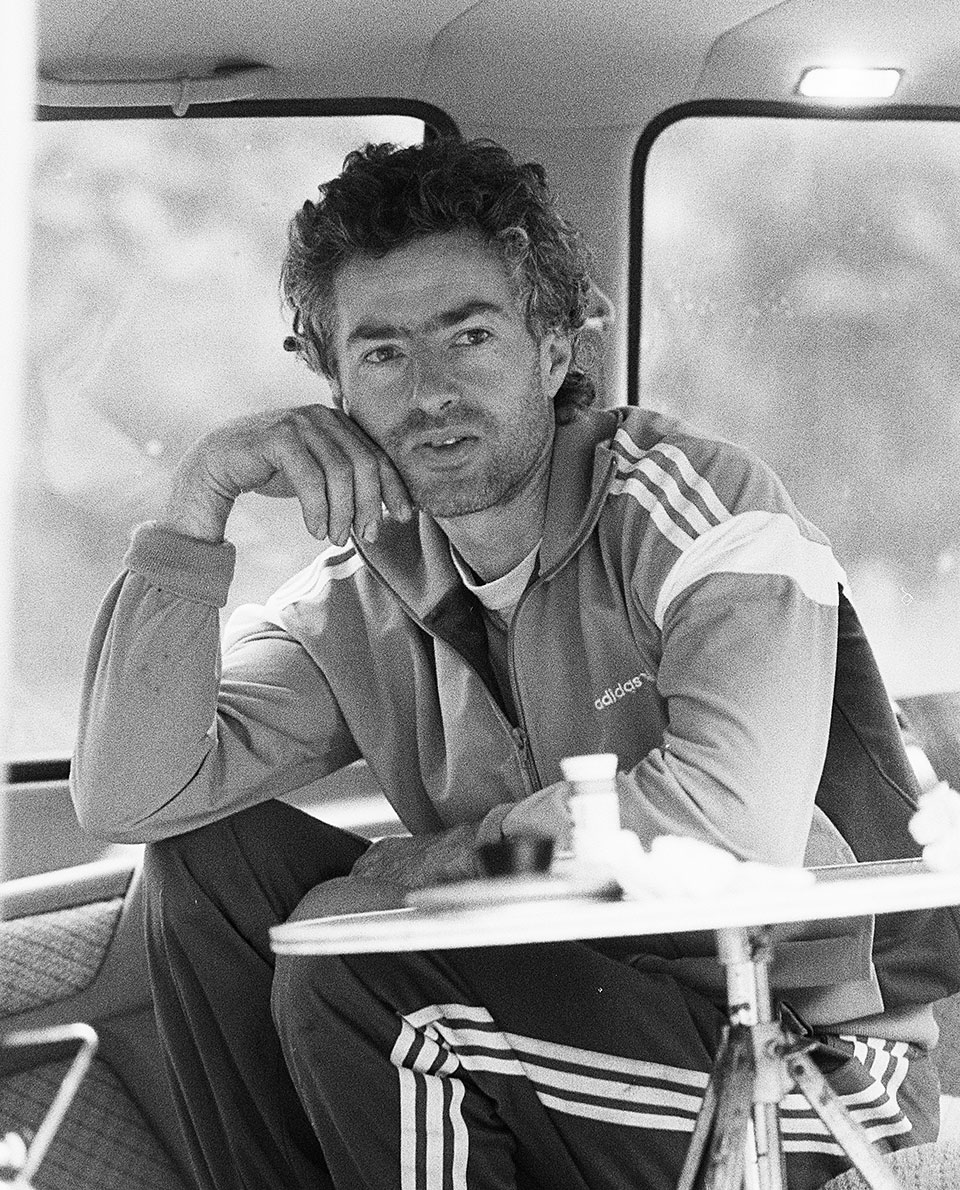

Our HANWAG Rotpunkt celebrates the bright colours of the 1980s and pays homage to the climbing pioneers who shaped an entire era. Sepp Gschwendtner was one of the most prominent climbers. As one of the first redpoint climbers, he exported the Redpoint (Rotpunkt) method from Bavaria to South Korea. Working as a tool maker at the time, he was also involved in developing HANWAG climbing shoes.

In connection with the redpoint revival, we interviewed Sepp Gschwendtner at his house in Deining, south of Munich. He offered us water or Red Bull to drink. Hanging on his living room wall, there are large black and white photos of Formula Vee racing (another of Sepp’s big passions), and the Tre Cime peaks in South Tyrol.

-

All about Sepp Gschwendtner

Sepp Gschwendtner was born in 1944 in Dorfen, near Erding, Upper Bavaria. He’s seen as one of the pioneers of modern sport climbing. He climbed ‘Münchner Dach’ in Altmühltal, Bavaria – Germany’s first ever grade 9 (UIAA) sport climbing route in 1981, wrote one of the first ever books about free climbing and went on to become a successful paraglider.

HANWAG is launching a retro-inspired mountain & leisure boot – the ‘Rotpunkt’. It’s popular in both outdoor circles and the fashion world. What do you think of it?

Sepp Gschwendtner: Being a practically-minded person, my first reaction was that it might need some changes to climb via ferratas. It could do with more of a climbing zone at the toe and a heel. But they told me that is not really what it is intended for. That it is more of a functional mountain and leisure model that you can also wear around town. Either way, it’s a good-looking shoe.

Does it remind you of your climbing days?

Definitely! It looks similar to HANWAG’s first ever climbing shoe. Though that had a shallow tread and was very smooth under the toe. It was a big success.

“It was a pretty cool scene. We used to do a lot of tightrope walking – these days they have slacklining.”

Sepp Gschwendtner

Bright, colourful, different – was this was the spirit and attitude of sport climbers in the early days of the 1970s and 1980s?

There were two main sources of inspiration for free climbing. One was the Elbsandstein sandstone towers in Saxony. The Elbsandstein area was the ideal training ground. They are not high-alpine mountains with all the associated dangers, where I have to admit I never felt that happy on long, multi-pitch routes. However, the routes there were very demanding psychologically. You’d reach the top completely drained after all the adrenalin. Elbsandstein is also one of the most beautiful areas in the world.

And what was the second source of inspiration?

America. It might have had a cool and relaxed image from the outside, but it wasn’t all like that. For example, in Yosemite the ranger would come into camp every night to check on things. This was much stricter than back in Germany. But it was a pretty cool scene. We used to do a lot of tightrope walking – these days they have slacklining. I liked the relaxed approach: meeting up, hanging out, without taking it too seriously.

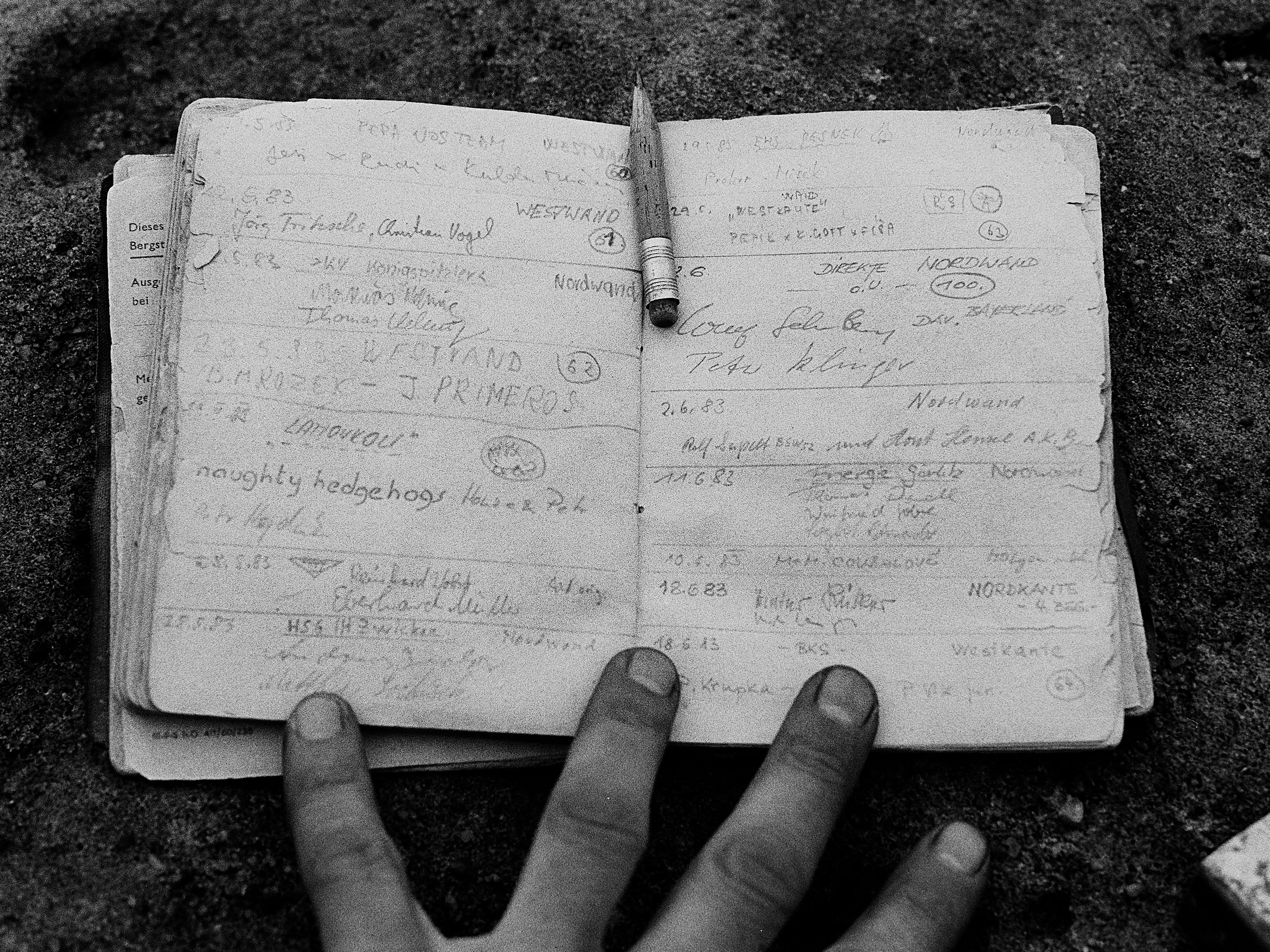

So is it true then, the cliché of climbers as wandering groups of artists moving from place to place?

Yep. If you went to Frankenjura, you would always bump into a bunch of climbers hanging up in a rockface. The same applied in the Joshua Tree National Park in California, the Verdon Gorge or Buoux in France, wherever happened to be the ‘in’ place to be. Although, there were routes there with names like ‘German, go home’.

Critics used to say that some climbers spent more time smoking joints than climbing routes.

Thinking back to the German scene, I would say that was not the case. However, in America, there were some pretty wasted characters. They were stoned the whole time and only seemed to get by because their girlfriends worked in the supermarket. It was a pretty wild scene. But it did mean that German climbers were able to catch up quickly with the climbing standards of the time – you see we lagged behind a bit. This became clear in 1981 during a climbing meet in Konstein. John Bachar came over from the US and blew us all away.

“Redpointing means climbing a route from the ground to the top without using ‘artificial aid’ to make progress and without resting on the rope.”

Sepp GschwendtnerWas redpointing in those days the ultimate form of climbing?

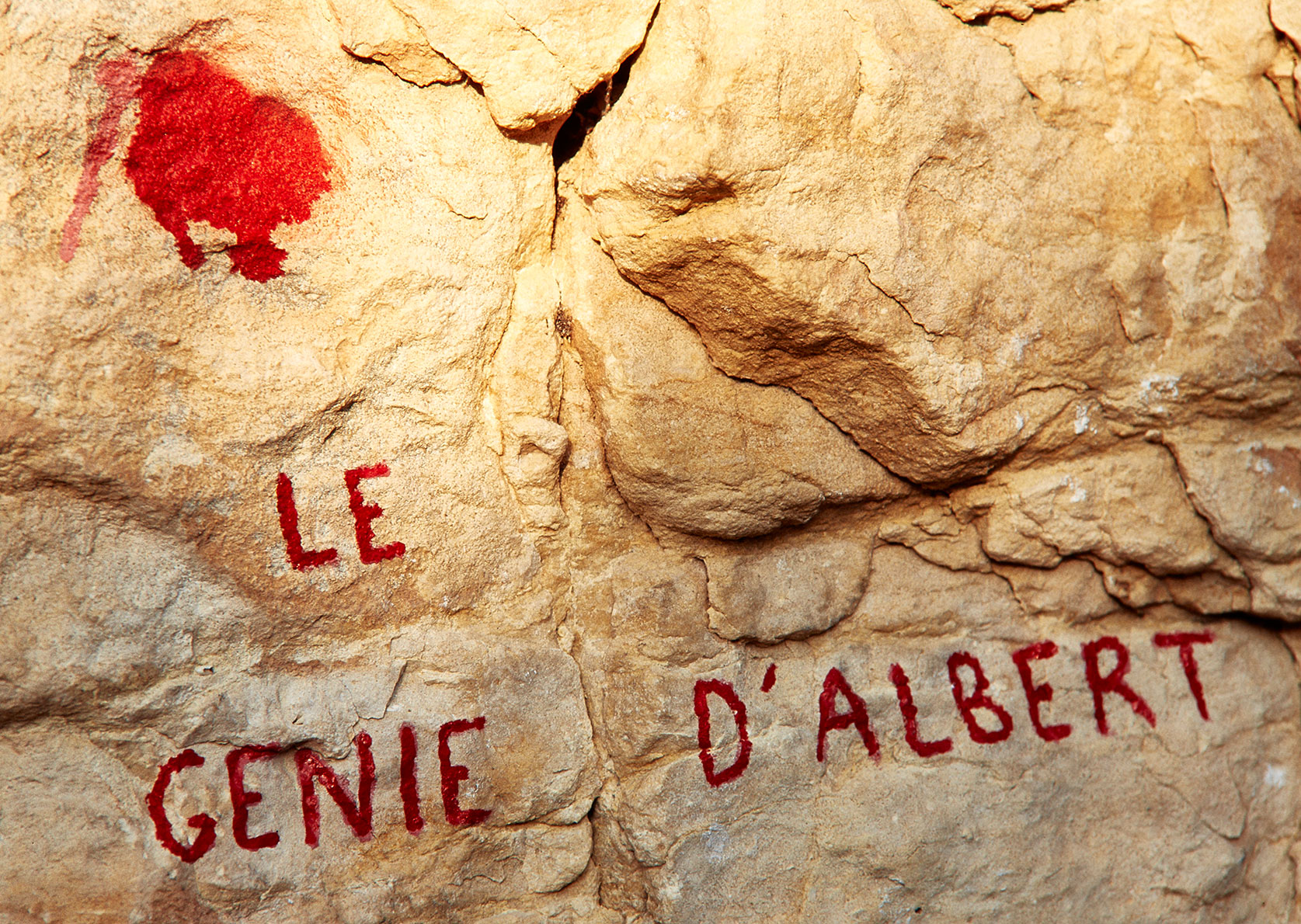

Free climbing opened up so many new opportunities. It meant we could climb thousands of new routes – first free ascents (FFA). And redpointing meant climbing a route from the ground to the top without using ‘artificial aid’ to make progress and without resting on the rope. We might have been pioneers of redpoint climbing and helped spread the redpoint movement, but the whole thing started with Kurt Albert – he invented it. He was one of a kind, I never heard him complain about anyone.

Always stay up to date: Subscribe to the HANWAG newsletter and become part of our community.

How did more traditional mountaineers view free climbing and redpointing?

Unfortunately, there were actually some good climbers who, to a certain extent, fought against it. It even went so far as the alpine safety expert Pit Schubert calling on my publishing house to not print my climbing textbook because it contained photos of climbers not wearing helmets. And in the Rheinland-Pfalz there was a massive row about using pitons, the Pfälzer Hakenkrieg. People used to remove pitons from routes. But then, this is not uncommon with new movements. Surfers were attacked by sailors, hikers argued with mountain bikers, and hang-gliders reacted in the same way to paragliders. It would seem that older generations often feel that they are being driven out.

Tell us about the ‘Magnesiawichser’ (chalk wankers) graffiti about climbers in Germany…

In the Altmühltal Valley, somebody painted the words “Magnesiawichser ins KZ” (Send the chalk wankers to the concentration camps). Though I find it hard to believe that mountaineers or climbers would say such a thing. The groups opposed to free climbing at the time were not that primitive. Many people realised that there was no stopping the rise of sport climbing.

“We didn’t want to look like traditional climbers.”

Sepp Gschwendtner

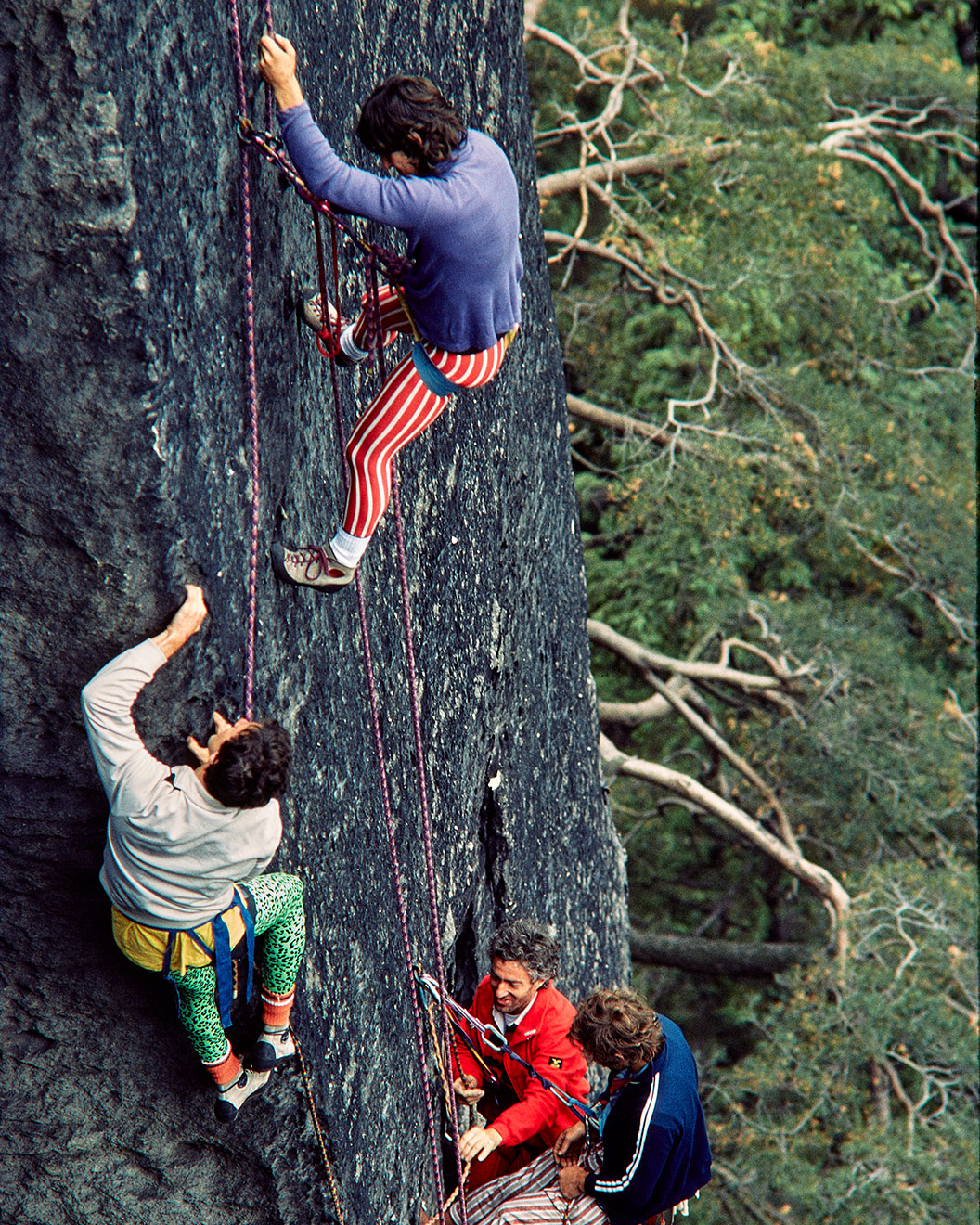

Back in the day, free climbers had their own look, which included wide shorts and bright, colourful tank tops. Was this a deliberate attempt to set themselves apart?

Our role models were top American climbers, not traditional mountaineers. I used to own a pair of baggy white cotton painter’s trousers, like the climbers in Yosemite used to wear. I wore them to climb the northeast face of Piz Badile and nearly didn’t make it because they got so soaked, they were literally hanging around my knees. Once, when I was hiking up to Ellmauer Tor in Austria’s Wilder Kaiser mountains wearing trainers and red Adidas tracksuit bottoms, I was told it was “suicide”. They said: “If you’re a mountaineer, you ought to look like a mountaineer.” Of course, this kind of attitude just spurred us on even more. One thing was absolutely clear – we definitely did not want to look like mountaineers.

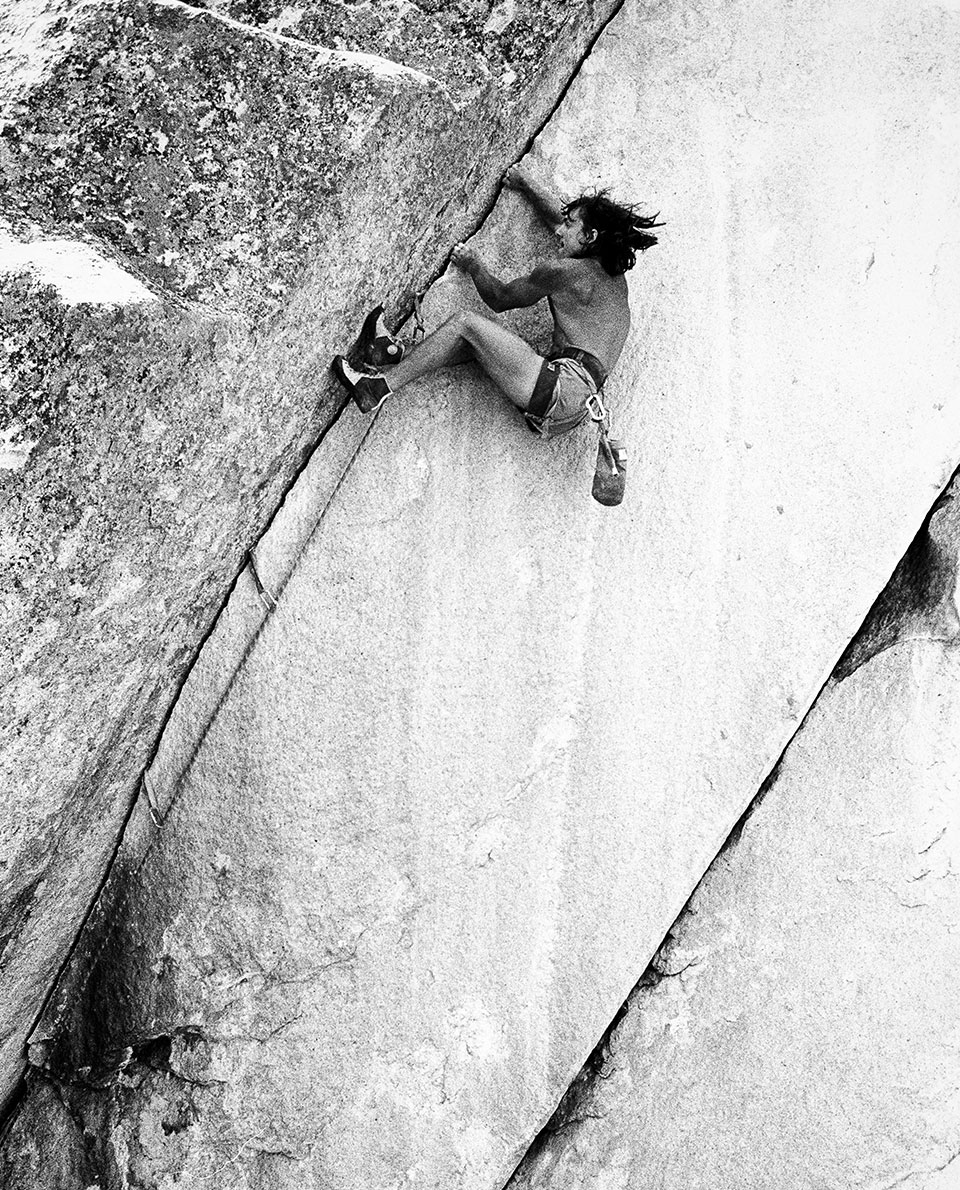

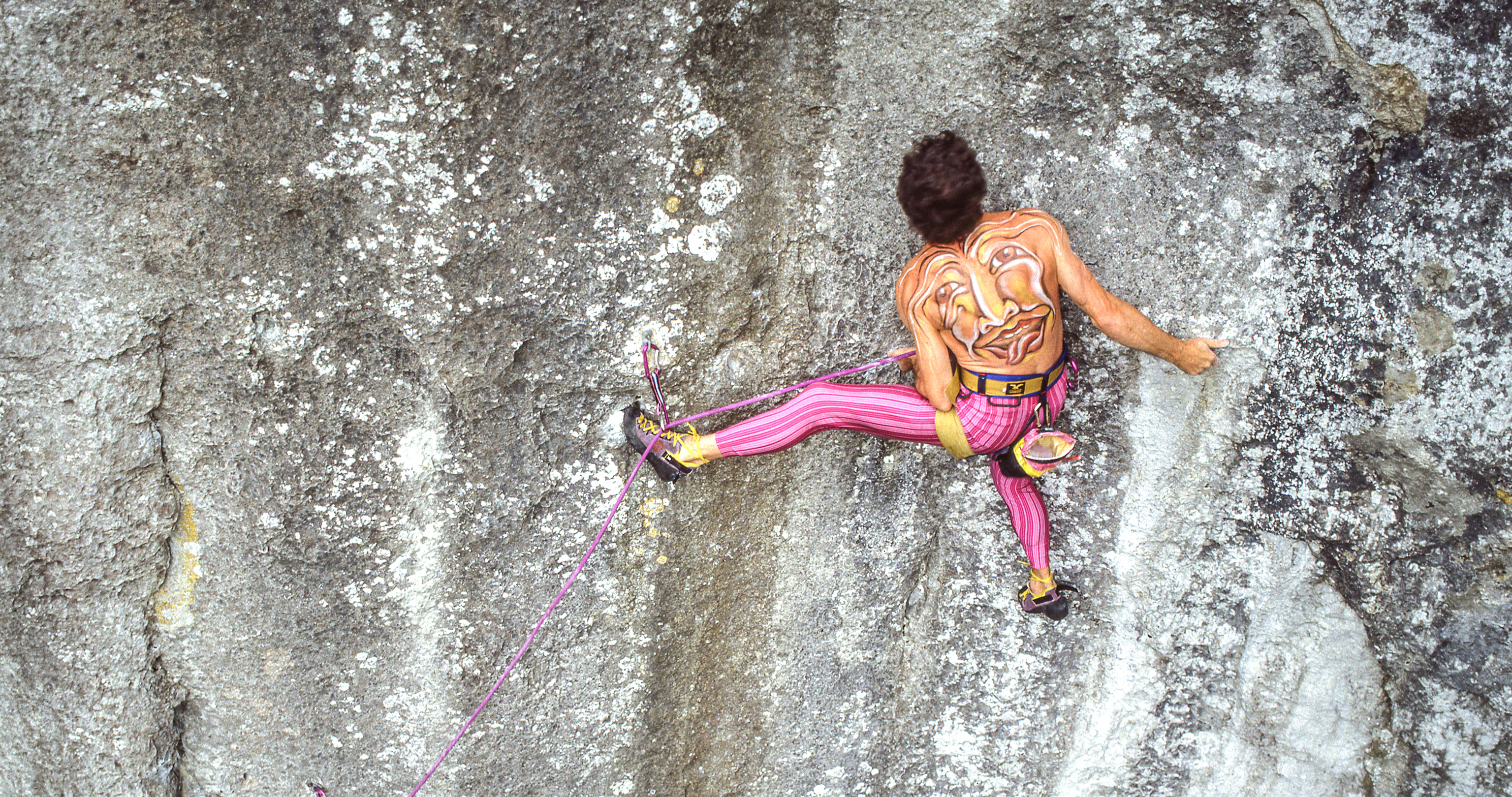

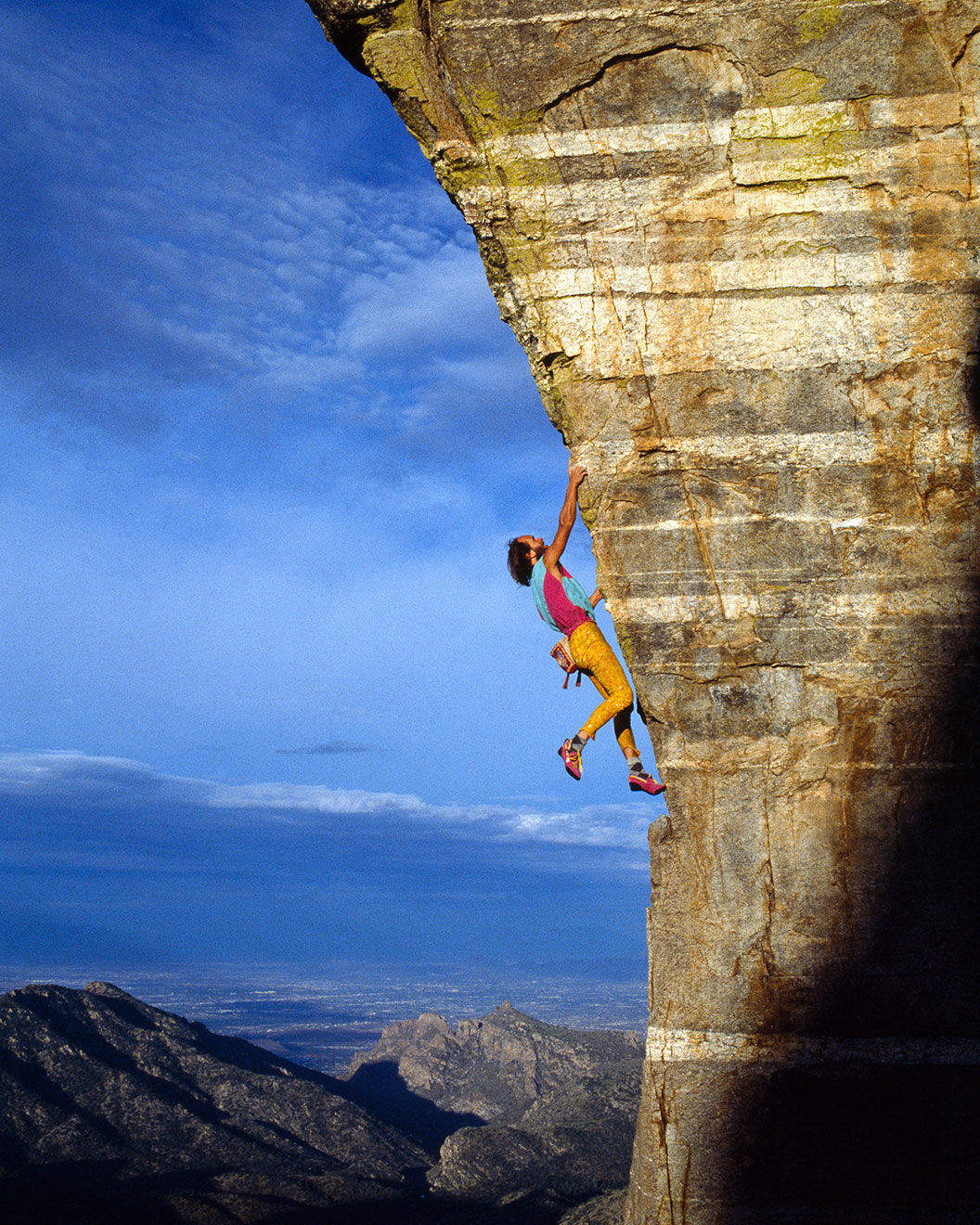

What about that photo of you wearing pink Lycra leggings with body paint on your back?

That had a different story behind it. It’s a photo by Heinz Zak, taken of me climbing ‘The Face’ a route in the Altmühltal Valley, my first ever grade 10 route and the hardest route I’ve ever climbed. The younger climbers at the time – Stefan Glowacz and his mates – said: “The old man is over 40, he’ll never make it.” That’s why, if you look at the face painted on my back, you’ll see that the tongue is sticking out. I can still remember though, it was pretty embarrassing going around clothes shops in Schwabing in Munich looking for leggings and trying to explain to the saleswomen what I wanted them for.

What did your first climbing shoes look like? Were they boots still or lightweight rock shoes?

When I started out climbing, we all wore stiff climbing boots. In the late 1970s, I got my first pair of EBs. A brand of climbing shoes with thin rubber soles. I had them sent over especially from the US. I added a small aluminium plate to mine to make them stiffer at the toe. I also experimented with using boxing shoes and sticking rubber from a lorry tyre inner tube to them. And then, together with the former HANWAG shoe designer Adam Weger, I helped develop the first climbing shoe for HANWAG.

A limited-edition legend: The HANWAG Rotpunkt retro boot

Back in the day, the first HANWAG Rotpunkt helped climbers, such as Sepp Gschwendtner to climb their hard, alpine routes. Today, with its retro-inspired styling, the functional mountain & leisure shoe has high-quality details such as a genuine leather lining and a Vibram sole. Available in three colour combinations. Get yourself a pair of the limited-edition shoes, each one has a unique embossed serial number. There will only be 999 pairs of the HANWAG Rotpunkt.

“I climbed ‘Münchner Dach’ wearing HANWAG shoes, proper climbing shoes with a thin rubber sole.”

Sepp Gschwendtner

What did you wear to climb hard routes, like ‘Münchner Dach’ in Altmühltal in 1981, and three years later when you climbed ‘Zombie’?

I climbed ‘Münchner Dach’ wearing HANWAG shoes, proper climbing shoes, with a thin rubber sole. They were good for hard climbs, I got on fine in them for a good while – until the English top international climber Jerry Moffat came to Germany, wearing the Boreal Firé, a Spanish climbing shoe. When it came to friction, they were so much better – a world apart. Their soles were made of natural rubber mixed with resin. This was then baked in an oven. To climb ‘Zombie’, I got Adam Weger to glue these Spanish soles to my HANWAG climbing shoes. But nobody was supposed to know. Luckily, HANWAG started to develop soles that were just as good, and we were back in business.

What did these new climbing shoes mean for the development of climbing as a sport?

They gave you so much more feel in your feet and this gave us massive confidence. It opened up a whole new world. From this point onwards, it was all about free climbing.

So when you see the new HANWAG Rotpunkt with its Eighties-inspired design, does it make you feel nostalgic and wistful?

I don’t think that things are that different today. In fact, a lot of things are better. Look, for example, at how things were for top climbers at the time, like Jerry Moffat. These days you can make a living from climbing. Today, I think athletes get much more recognition. Having said that, it’s not always easy being a professional athlete – you have to be able to cope with the pressure.

So it’s not a case of everything used to be better in the old days?

Definitely not.